What exactly is respect and how does it differ from courtesy? Find out in this article by Dr Laura Olcelli and Robert Ace.

Friday, 4 p.m. We are in our usual training room. Everybody’s excited the working week is coming to an end.

The moment we mention the topic of our current research and ask our group to complete a brief questionnaire, several delegates inevitably begin humming the popular 1967 tune: “R-E-S-P-E-C-T / Find out what it means to me”. It’s all laughter. Thank you, Aretha Franklin!

50 years later, we’re still pondering on this powerful word and its true meaning: what is respect? How does it differ from courtesy? How much of both do we expect and give? And do men and women, young and less young share the same opinions?

Lost in definition

We analysed the definitions given by a sample of 167 customer service agents of a UK Government Agency, and discovered that the distinction between ‘respect’ and ‘courtesy’ is not obvious.

Courtesy

The concept of courtesy is straightforward and well understood. There are no doubts the first word that springs to mind when we think about courtesy is ‘polite’. This reflects the dictionary definitions of politeness, good manners (Collins), and the showing of politeness in one’s attitude and behaviour towards others (OED).

Fig. 1.1: Word cloud for ‘courtesy’.

Respect

When it comes to respect, things become more complicated.

Overall, the delegates identified the main aspects of respect as treating others fairly, or understanding and appreciating others’ opinions and views. These definitions are rather divergent from the actual meaning of attitude of deference, admiration, or esteem (Collins), or a feeling of deep admiration for someone or something elicited by their abilities, qualities, or achievements (OED).

Fig. 1.2: Word cloud for ‘respect’.

Given the discrepancy between the actual and perceived meaning of respect, we also explored any differences in the definitions given by men and women.

Some gender differences came to the surface: in the definitions given by women, there’s a greater emphasis on words such as ‘feelings’, ‘empathy’ and ‘listening’, which are hardly readable on men’s word cloud.

Fig. 1.3: Word cloud for ‘respect’ from male staff.

Fig. 1.4: Word cloud for ‘respect’ from female staff.

This shouldn’t come as a surprise: research has long shown that female brain is primarily hard-wired for empathy, and female communication tends to include more emotional references than male’s (see, for example, the work of Simon Baron-Cohen and Anthony Mulac and associates). So it’s understandable this is also visible in women’s definitions of respect.

Nonetheless, the core of the definition remains inaccurate – from both sides. Words that we’d expect to read in the dictionary definition of respect, such as admiration for someone’s skills, are virtually unmentioned. Some synonyms (like high-regard and appreciation) are present to a much lesser degree, especially in men’s definitions.

This is quite significant, especially when considering the implications: do internal customer experience and satisfaction measurements rely on our personal interpretation of the notions of respect and courtesy?

Respect or courtesy?

We went on to examine what people say they’d rather have from the companies they deal with every day.

Our data reveal that respect is almost a third more desirable than courtesy, and this probably has to do with the widespread distorted interpretation of the concepts of respect and courtesy.

But are there any variations between men and women, or in terms of age?

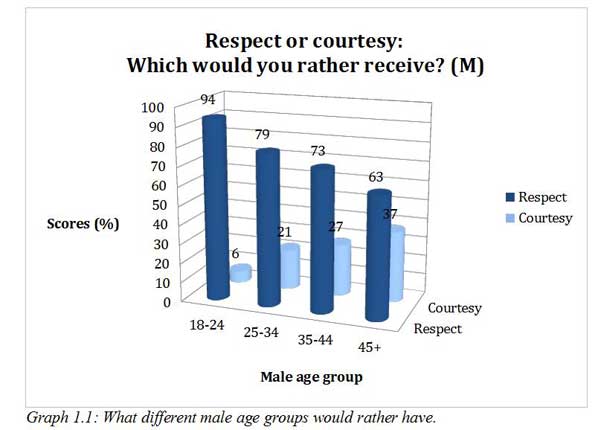

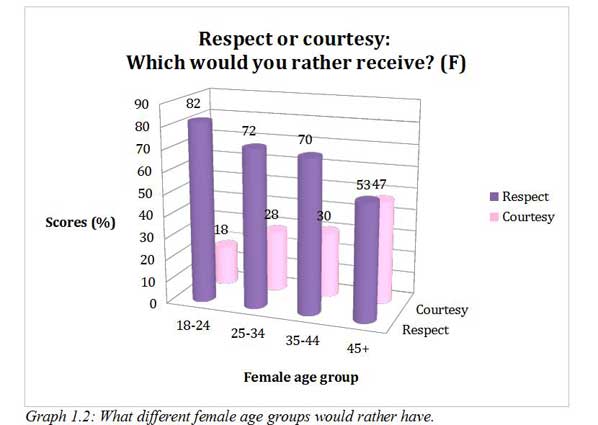

Although both men and women in all age groups claim they’d prefer to receive respect over courtesy, as graphs 1.2 and 1.3 show, courtesy becomes increasingly more desirable with age, for both sexes.

What’s more, on average across all age groups, courtesy is more significant for women (30%) than for men (23%).

Interestingly, while 18-to-24-year-old men disclose a strong preference for respect (94%), women over 45 years of age score the highest percentage on want for courtesy (47%).

A generational gap seems to emerge: young people are not overly concerned with good manners, and would rather have their opinions recognised and appreciated. This is particularly evident in young men. However, the older generations are not willing to completely give in: women in particular still expect and appreciate good manners.

What can companies learn?

In today’s increasingly competitive market place, there’s more pressure than ever on providing an excellent customer service, increasing sales, and reducing complaints. All of this links to a greater discourse on loyalty, trust, and of course profitability.

So what do these results on respect and courtesy mean for companies?

Organisations might think courtesy and politeness are commercial imperatives. And indeed they are. But the discerning customers of the 21st century also want something else from the companies they deal with: R-E-S-P-E-C-T.

In the 1960s, Aretha Franklin sang about respect “Find out what it means to me”. Today, we’ve come to understand that, from a consumer’s perspective, the denotation and connotation of respect don’t correspond. For customers, respect also implies being treated fairly, listened to, and ultimately feeling that their opinions are being understood and valued.

This highlights the need for companies to adapt the way they talk and write to the changing needs of modern customers, and to further tailor these to different sexes and age groups.

About the Authors

Dr Laura Olcelli is a Learning & Development Professional, Researcher and Translator whose interests and publications encompass the fields of communication, languages and literatures. She has studied and worked across three continents, and she is currently a Training & Development Consultant at T2uk, the world’s leading provider in the commercial application of Psycho-Linguistics.

Robert Ace (BSc Hons, PGCE, MBA) was educated at Portsmouth, Oxford and Edinburgh Universities. He has experience across a broad range of industries including working with blue-chip companies in the Utilities, Media, Hospitality and Finance sectors. His areas of expertise include performance management, corporate training, and cultural change.

To find out how Psycho-Linguistic strategies can enhance your corporate communication and improve your customer service, visit www.t2-uk.com.